For the Public

- Common myths or unappreciated facts regarding bacteria or genomics

- Bacterial Genomics 101

- Lab research overview

Common myths or unappreciated facts regarding bacteria or genomics

A few facts regarding genomics, bacteria, and bacterial diseases that are often misunderstood or not appreciated.

Bacteria

Not all are bad. The vast majority of bacteria in our world are harmless to humans, and many are beneficial.

Life on earth would not function without bacteria. Bacteria provide many needed nutrients for our survival and the survival of other animals and plants.

Bacteria on our bodies can actually protect us from disease. We are covered with “friendly” bacteria (called our “normal flora”) that tend to take up “space” on our skin and in our gut, making it more difficult for disease-causing bacteria to gain a foothold on us and cause a harmful infection. Our first exposure to such friendly bacteria at birth provides our new immune system with important early exposure to bacteria, so our bodies can learn to control them.

Amazing but true! The average adult person is estimated to contain more bacterial cells than human cells! (The lowest estimate of bacterial cells is higher than the highest estimate of human cells). A rough estimate of the number of different bacterial genes inside us (based on the estimated number of species, and assuming ~2000 genes per species) is more than the highest estimate for the number of human genes in the human genome. We would do well to learn more about the bacteria on and in us that are such a significant part of us!

Harmful bacteria don’t affect all people the same way. For this reason, it’s often hard to tell whether something you did or took helped to make you better or kept you from getting a certain infection. This is why researchers often study large groups of people to determine if, on average, more people are helped by a certain treatment than another group of people given no such treatment.

Bacteria can develop resistance to antibiotics, so that the antibiotic becomes unable to control the bug. Antibiotics must therefore be used exactly as prescribed (i.e. take all the pills at the correct dosage and frequency per day – don’t stop taking the medication just because you start to feel better).

Antibiotics can be effective against bacteria, but not viruses. Antibiotics do nothing to help a cold or flu and should only be used when really needed. Not only does such inappropriate use of antibiotics increase the risk of antibiotic resistance forming, but also antibiotics don’t just kill harmful bacteria – they also kill many of the “friendly” bacteria on our body too. Therefore this disruption of the “friendly” bacteria (normal flora) can increase your risk of developing subsequent infections with other microbes that may not have otherwise have been able to infect us.

We have little understanding of our microbial world. We have traditionally been studying primarily those bacteria that we can grow in the laboratory, however it is now becoming apparent that there are many more bacteria on our bodies, and in the environment, that can not grow in traditional laboratory media used to grow microbes. These bacteria remain to be studied by other methods (such as analysis of their DNA sequence).

Genomics and Bioinformatics

Bioinformatics is not that new. Ecologists, evolutionary theorists, and other biologists have long been using informatics to aid biological analysis. With the first sequencing of proteins in the late 40′s, early 50′s, and Margaret Dayhoff’s Atlas of Protein Sequences in the early 70′s, the foundation was set for bioinformatics as it’s known today. The first complete genomes (of bacteriophages, which are viruses of bacteria) were sequenced in 1976-77.

Bacterial Genomics is different in notable ways from most other Genomics fields (for example, human or plant genomics). Bacterial genomes are much smaller than animal and plant genomes, and so they can be sequenced more quickly. It is also easier to computationally identify the genes in bacterial genomes, and it is easier to disrupt and otherwise manipulate the genes to learn about their function. That doesn’t mean that bacteria are less complex – bacterial genes are packed more closely together in their genome than, say, in the human genome, and the genes still appear to interact with each other in complex ways. However, we are only beginning to understand how complex life really is.

Bacterial Genomics complements other microbiology fields. Genomics and bioinformatics are relatively “hot” fields right now, but they should be kept in context. They are a way of studying life that has its own benefits and disadvantages. They complement more traditional microbiology approaches to studying bacteria, which are still very necessary.

(For information about Bioinformatics in Canada, in particular bioinformatics researchers, programs, courses, events, and jobs, see Bioinformatics.ca)

Bacterial Genomics 101

Don’t understand what the heck a genome is?

(by Fiona Brinkman, with the first half of the information partially derived from the the Oak Ridge Laboratories “Genetics 101″ resource)

Bacterial Genomics is different in a number of ways from genomic studies of eukaryotes (eukaryotes are the group of organisms that includes plants and animals). There are a number of excellent resources describing the Human Genome Project and human genomics, but these resources are not completely applicable to bacterial genomics. Therefore, this summary has been written to aid understanding of Genomics in the context of bacteria.

What is Bacterial Genomics?

Generally, bacterial genomics is a research field that studies the genome of bacteria, or studies bacteria using approaches or technology derived from understanding the bacterial genome and its DNA sequence.

What the heck is a genome and DNA sequence?

The complete set of instructions for making any organism is called its genome. It contains the master blueprint for all cellular structures and biological processes for the lifetime of the organism. A copy of the genome is found in each bacterial cell, and it consists of two tightly coiled threads of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) organized into structures called chromosomes. To use an analogy, think of the genome as the “encyclopedia” of all instructions on how to make an organism. Chromosomes are equivalant to the different volumes of an encyclopedia. Many bacterial cells contain just one chromosome (their “encyclopedia” is only one book), however some have more than one, and humans have 24 chromosomes (i.e. equivalent to a 24 volume encyclopedia, to use the analogy).

If unwound and tied together, the strands of DNA for the genome of a human would stretch more than 5 feet but would be only 50 trillionths of an inch wide. However, through tight packaging, the DNA containing a copy of the full genome is packed into a single cell (all life is made up of units called cells). Likewise, in bacteria all the DNA for the complete genome is packed into each – even tinier – cell.

Each strand of DNA is a linear arrangement of similar repeating units, often termed bases (think of these as the “letters” in an encyclopedia). Four different bases are present in DNA: adenine (commonly referred to as just “A”), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (you guessed it, G). The particular order of the bases is called the DNA sequence. The sequence specifies the exact genetic instructions required to create a particular organism, including a particular bacterial species, with its own unique traits.

The two complementary strands of DNA are held together by weak bonds between the bases on each strand, forming base pairs (bp). Think of these complementary strands as “two copies” of the encyclopedia (so that if one copy is damaged, the there is another copy to refer to). Genome size is usually stated as the total number of base pairs (bp). The human genome contains roughly 3 billion bp. Bacterial genome sequences determined by the turn of the century (year 2000) range in size from approximately half a million bp, to 8 million bp.

Note that each time a bacterial cell divides into two daughter cells, its full genome is duplicated (both strands of the DNA). Therefore, each new bacterial cell produced contains a new copy of the genome sequence (that contains the two complementary strands). This genome sequence (encyclopedia), comprised of base-pairs (letters) is full of genes (which can be considered the “words” in an encyclopedia).

What are genes?

Each DNA molecule contains many genes. A gene is a specific sequence of base pairs (bases, or “letters”) that contains the information required for constructing a protein (in most cases). The proteins encoded by the genes provide the structural components of the cell as well as enzymes for essential biochemical reactions. In other words, proteins are not just in the food we eat: They are the building blocks of life and are main components of our cells. Genes are the “words” in our genome “encyclopedia” that form the instructions for constructing these proteins. The human genome is estimated to comprise approximately 30,000 genes, while different bacteria can have as few as approximately 500 genes, or as many as 6000 genes or more. Proteins are large, complex molecules made up of long chains of subunits called amino acids. Twenty different kinds of amino acids are usually found in proteins.

So how can we build proteins comprising up to 20 different amino acids, if the code within genes for building them only comprises 4 bases? Well, it turns out that special proteins in our cells examine the genes’ code in “triplets” of three base pairs at a time. Each “triplet” of three base pairs codes for a particular amino acid. The genetic code to make a given protein is thus a series of “triplets” of three bases in a gene that specify which amino acids are required to make up specific proteins. A collection of triplets that make up a protein is called a gene, and the collection of genes that make an organism is called its genome.

Studying Genomes:

Since a bacterial genome contains all the information for building and running a cell, there has been considerable interest in determining the DNA sequence for the genomes of bacteria, particularly for those bacteria that cause disease. We hope that by knowing the code for what makes bacteria tick, that we may be better able to come up with means to:

- control them (for example, if they cause disease)

- maintain them (for example, if they are important for our environment)

- use them for beneficial purposes (for example, industrial spill cleanup or making products)

So, technology has been developed to determine the complete DNA sequence (“all the letters”) of a genome, using machines that are called (aptly) DNA sequencers. For bacteria, genome sequences had been obtained for approximately 35 different bacteria by the turn of the millennium, with the first genome sequence for a bacteria determined in 1995. Many more bacterial genomes are being sequenced and so databases have been formed to contain all the DNA sequence information (as long strings of A’s, T’s, C’s and G’s). In addition, early research determined what triplets of of the DNA bases encode what amino acids, and so that we can predict from a bacterial genome sequence what proteins it may encode. Both the DNA sequence of bases, and the protein sequences of amino acids, contain additional “strings” of sequence within the DNA or protein that specify particular functions and/or act as signals for the bacteria.

So, what does Bacterial Genomics do?

Bacterial genomic approaches to studying life include determining the DNA sequence of a given bacterial genome, comparing the DNA sequence with other genome sequences, and deciphering what the genomes encode (predicting what makes up an organism from its DNA sequence). The whole gene complement of different organisms can be compared with one another, detecting, for example, genes specific to certain disease-causing bacteria that may be targets for drug therapy or for diagnostics. This field of research also attempts to study bacteria on a “whole-organism” scale. It takes a more holistic view regarding how the genes and proteins function and work together, or what genes or proteins are necessary for a certain function (such as causing disease). This whole-organism approach is quite different from the early approaches microbiology used to study genes and proteins: Classically, single genes or proteins were studied on a (relatively) individual basis, with little understanding of how all the genes and proteins in a cell worked together. Genomics and associated “omics” studies attempt to gather information regarding how the full complement of genes (or proteins or metabolities etc) in an organism work together. It is thought that such an approach to studying bacteria, and in fact all life, will complement the classical, but still very necessary, studies that are focused on particular genes or proteins.

What will Bacterial Genomics give us?

Bacterial genomics can give us a broader understanding of how a bacteria functions, a bacteria’s origins, and what bacteria live in our world that we can’t study by other means (i.e we may not be able to grow it up in the lab, but through obtaining their DNA from the environment we can still study it). Of medical interest, bacterial genomics is also anticipated to play a significant role in speeding up the development of better therapies and vaccines for controlling disease-causing bacteria. It will also be the cornerstone of anticipated DNA-based diagnostic tools that will hopefully enable doctors to make quicker, more accurate diagnoses of infectious disease. Most recently, bacterial genomics, through the tracking of base-pair changes that can semi-randomly occur in a bacterial genome over time, is allowing us to better track the spread of infectious disease in communities and worldwide. There is increasing interest in using genomics as a key component for better tracking infectious disease spread, leading to more rapid implementations stop its spread (for example, during foodborne infectious disease outbreaks).

It is an exciting time to be a bacterial genomicist (and bioinformaticist – those who computationally study the data). There is so much to be done, so much to learn, so much to discover! So much potential too for real differences to be made that will improve the health of people, other living things, and our environment. In fact, change for the better is already happening, but stay tuned for much more!

Lab research overview

Our laboratory is using computer-based analysis, combined with laboratory experimentation, to gain a better understanding of how some bacteria and other microbes cause disease. We are interested in learning how bacteria evolve from harmless microbes to bacteria that cause a harmful infection. We hope that by understanding how bacteria change their disease-causing properties over time, that we can gain a better understanding of the mechanisms by which bacteria cause disease, and be able to develop more sustainable approaches for infectious disease control.

We are also using our computational approaches to aid studies of the role that environmental and social activities play in the development and spread of infectious disease, as well as the role of our immune system. Our approaches have increasingly become more holistic, as we investigate the role of the microbe in causing infectious disease in the context of the host, society and environment.

We are also interested in developing better ways to predict, using computers, what components of a given disease-causing bacteria are most likely to play a role in infection, or be suitable drug targets, vaccine components, or used in diagnostics. This helps us and others prioritize what components, including genes, to study further in the laboratory (“genes” are, in general, the portions of DNA in the bacteria that encode the instructions to make the different components of the bacteria). We are also interested in predicting what components of a bacteria are located on its cell surface. Such components, being on the cell surface, are more easily accessible and so can be primary targets for the development of new infectious disease drug treatments and vaccines. We have been identifying and prioritizing potential anti-infective and antimicrobial drug targets and vaccine components, as well as predicting key targets in our own human body that could boost our immune system against infectious disease.

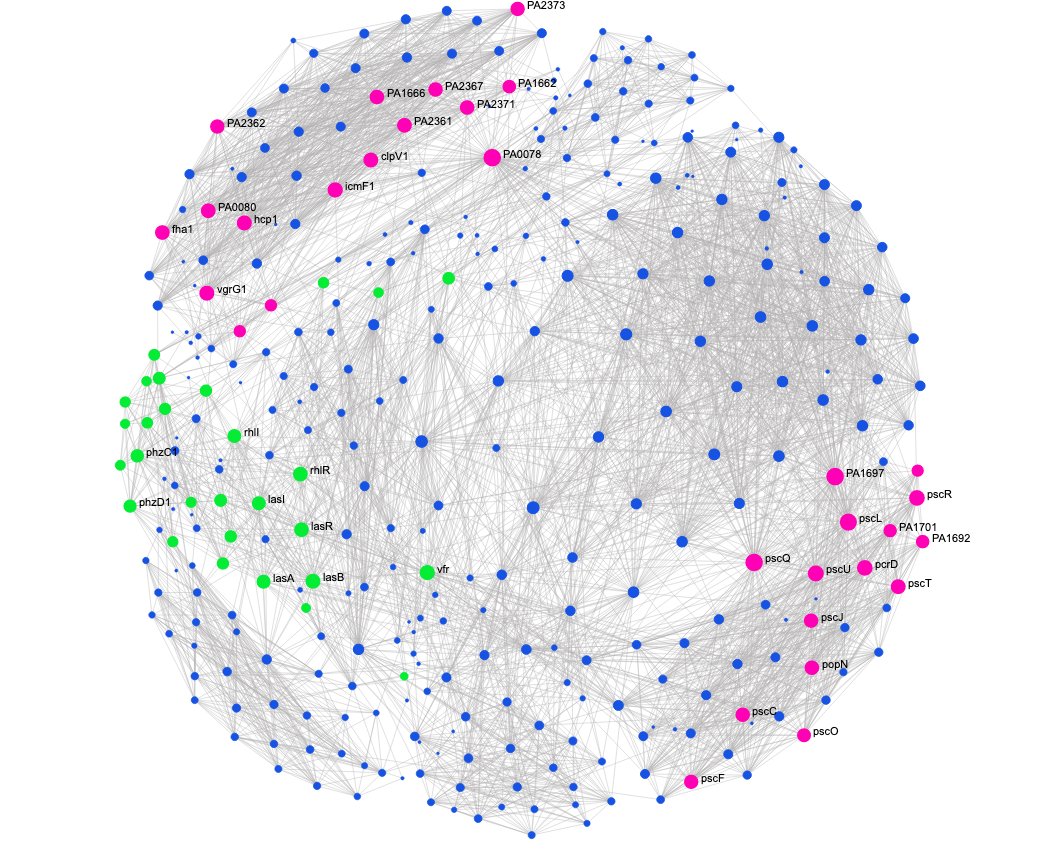

To do this, we are studying complete DNA sequences (“the genetic code” or “genome”), for certain disease-causing bacteria. This genetic code contains the “blueprint” for each particular bacteria (i.e. all the genes that make up all the components of the bacteria are contained in this code). We are studying this DNA code using computer analyses, and are then generating predictions about how the bacteria function and what proteins they make from these analyses. Certain hypotheses are tested in the laboratory and some are tested through further computer-based analysis. We also performing analyses that integrate additional data and use a more “systems biology” or network-based approach. This approach looks at the cell as a network of molecules, identifying key components in the molecular network that could be targeted to better control an infectious disease. We can also apply a network-based approach to look at whole populations of people – identifying ways in which we can better control infectious disease at the societal level.

There is currently a massive amount of DNA code in research databases worldwide – essentially a backlog to be analyzed – and so important discoveries still remain hidden in the code. The Brinkman Lab hopes to gain new insights about harmful bacteria, the diseases they cause, and possible new treatment approaches, through an interdisciplinary approach that uses the resources of both a microbiology laboratory and computer facilities